Wrapping Up and Looking Ahead

posted by Chris Kruger

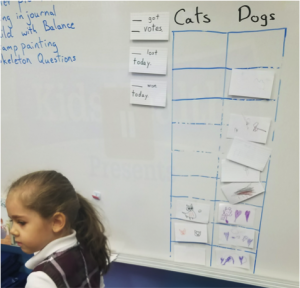

So far, we’ve seen what it takes to prepare an exploration, a graphing progression, and a discussion about what kind of questions can be centered around an exploration. To wrap up our month, I’m going to extrapolate from a specific example to a general framework for explorations.

A General Framework for Explorations

One of the most fundamental aspects of an exploration is the materials the students use. In the graphing exploration, the materials mainly stayed the same, index cards or paper pie slices and tape. Other explorations, however, can be greatly varied based on the material. For example, say I wanted to lead an exploration about how textures impact painting. If I wished to alter the materials, I would change what they used. Maybe one day we would paint on standard paper, then silk to see a smooth texture, and then painting on tree bark to see how that differed. Conversely, we could paint every day with a different substance mixed into the paint (rice, sand, and then flour) to see how the texture of the substance affected their art. Especially with young children, they are very sensitive to changes in the physical materials they use and benefit from these varied exposures. In my experience, these are the easiest pieces of an exploration to change.

One of the most fundamental aspects of an exploration is the materials the students use. In the graphing exploration, the materials mainly stayed the same, index cards or paper pie slices and tape. Other explorations, however, can be greatly varied based on the material. For example, say I wanted to lead an exploration about how textures impact painting. If I wished to alter the materials, I would change what they used. Maybe one day we would paint on standard paper, then silk to see a smooth texture, and then painting on tree bark to see how that differed. Conversely, we could paint every day with a different substance mixed into the paint (rice, sand, and then flour) to see how the texture of the substance affected their art. Especially with young children, they are very sensitive to changes in the physical materials they use and benefit from these varied exposures. In my experience, these are the easiest pieces of an exploration to change.

A second aspect of an exploration that can be altered is the constraints placed on the students. Constraints, as generally understood, are restrictions on how students can use their materials. This is an overlooked aspect, as teachers generally only restrict the final product students can create or the general amount of time that can be spent on an activity. This is shortsighted, as there are incredibly nuanced and powerful changes that can result from properly applied constraints. In the graphing exploration, the class had constraints based on who they could vote for, how they voted, and the representation of their votes. To continue with the painting and texture example, students could paint with their eyes closed to see how the slick paint felt when spread over the rough paper. While the distinction between materials and constraints may be nebulous at times, it remains a valuable lens through which to view explorations.

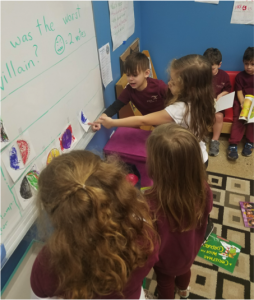

The final aspect of an exploration is the focus of the students, which is directly impacted by you the educator. Through your questioning, you help students realize what they should be paying attention to or thinking about in an experience. To be clear, students can and will surprise you by noticing things you never expected, but it is also important to plan an exploration around key questions and vocabulary. For example, in the graphing exploration, I drew students attention to the relationships between the numbers of votes instead of just who had more. In the painting and texture example, the focus would include questions like “How does this feel different than that” and “How did this texture affect your painting”. Focus work would also include highlighting vocabulary that would be useful, like ‘rough’ or ‘smooth’ in the texture example. This questioning and vocabulary should expand as the exploration progresses, encouraging the students to think more deeply or analytically about the process.

Some Examples of the Framework in Action

In general, I have found it best to alter either the products OR the constraints day to day, not both. This allows the students to more easily reflect on a specific change from the prior activity. This is not a hard and fast rule, just a general guideline.

In order to provide a launching off point for future explorations and help explain the three aspects of an exploration, here are couple of examples of explorations and how their aspects can be modified.

Building

Building

-Materials: unit blocks, legos, paper towel tubes, rocks

-Constraints: goal (height, representation of specific object, volume), time limits (15 seconds, 30 seconds, 1 minute), blindfolded, only using one hand

-Focus: “Is it easier to have a wider base or a narrower base?”, “Do you think you’ll be able to build as much in 30 seconds as you did in 1 minute?”, balance, symmetry

Color

-Materials: shading paint (a single color with black and white paint to alter shade), colored paper, stained glass (tissue paper on a light table), magnetiles and flashlights

-Constraints: painting in colored lenses or light, painting in dim light (colors appear washed out and gray), colored shadows

-Focus: “How did you make that color, since I didn’t put out any orange?”, “Why doesn’t this look as red as it did on the white paper?”, shade, blend

Hopefully, with this framework and these examples, you’ll be able to take a great idea and expand it into a full-fledged exploration. After all, there’s nothing wrong with doing something fun!

I like that there are examples in all of these topics. It helps to wee this and makes more sense.

thank you.